World Innovation Lab connects startups and corporations, leveraging its LP network to drive global expansion and growth.

According to a series of key metrics, Japan’s start-up scene has experienced a significant bull run over the past decade. The number of deals has doubled since 2013, and investment amounts have surged tenfold to reach JPY 850 billion in 2023. Moreover, the sector has achieved several high-profile successes that have drawn global attention. Since Mercari reached a valuation of JPY 670 billion in 2018, 12 companies with valuations exceeding JPY 100 billion have gone public. What key factors do you believe have driven this decade-long bull run? Additionally, how do you foresee these metrics evolving over the next two years?

From my perspective, there are a few key points worth highlighting. First, the role of the government has been a major factor—an influence that’s quite unique when compared to other countries. Around a decade ago, during the tenure of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, the government introduced policies that focused specifically on startups. These policies were part of a broader framework referred to as the Japan Revitalization Strategy. The Prime Minister Abe was the first leader to prioritize startups, something none of his predecessors had done.

I recall a meeting with him during his visit to Silicon Valley. We discussed how Japan should embrace entrepreneurship more actively and offered my support for his policies by helping Japanese entrepreneurs connect with the U.S. market. At the same time, I offered to encourage U.S. and European entrepreneurs to explore opportunities in Japan, explaining that welcoming foreign entrepreneurs would create synergy and ultimately benefit Japan’s market. I emphasized that this is a realistic opportunity as that was the work I was already engaged in and hoped to continue. This conversation marked a pivotal moment, as it helped bring the term "startup" into official government discourse. It demonstrated how much influence the Prime Minister's vision and advocacy could have.

The media played a crucial role in the next phase of this shift. Over time, they began recognizing startups as legitimate businesses rather than fringe ventures. This recognition was vital for fostering public and institutional support for entrepreneurship as a driving force for Japan's economic growth.

In my view, this transformation began about ten years ago, and the government’s endorsement was a catalyst. Venture capital funding has since increased tenfold. Before this change, startups often operated on the periphery of society, perceived as ventures for those who couldn’t secure roles in prestigious companies or attend elite universities. Unfortunately, startups were often seen as the domain of “losers.” Still, even within that perception, a few standout successes helped keep momentum alive, motivating those in the ecosystem to persist.

Despite the inherent challenges of startups—low success rates, long timelines, and various barriers—those involved were driven by a desire to change the world. Today, the narrative has shifted dramatically. Saying, “I’m going to invest in startups” is now met with government support and encouragement. Leading universities are actively promoting entrepreneurship, launching their own venture funds, and investing in their students' ideas. This cultural shift has been significant, allowing firms like ours to operate more like U.S. venture capital firms.

This change has also legitimized the venture capital industry, enabling it to grow by removing barriers to fundraising and investment. I like to think the government’s proactive stance acted as the trigger, unleashing the talent and potential within the startup and venture capital sectors. It was the desire to catalyze this shift that inspired me to establish my own company 11 years ago.

When a new industry emerges, its growth can appear rapid simply because it starts from a low baseline. That’s perfectly fine—we all have to start somewhere. The key, however, lies in sustaining this momentum. The government’s bold targets and support, such as deregulation and new laws, have been critical in creating a foundation for continued growth. As companies operate in this space, we must believe in these ambitious goals and focus on planning the path to achieve them. Without belief, progress isn’t possible. The synergy between government backing and industry effort has been—and will continue to be—essential to maintaining this upward trajectory.

Japan has indeed faced criticism for its low entry and exit rates in comparison to other developed nations. Historically, this has been tied to a cultural hesitation toward entrepreneurship. Surveys consistently show that over 65% of U.S. and Chinese citizens view entrepreneurship as an attractive career path, whereas the figure is notably lower in Japan. How do you foresee these attitudes shifting in the coming years? Additionally, what specific initiatives is your company undertaking to promote entrepreneurship and help change these perceptions?

Social inertia, as I mentioned earlier, is deeply tied to cultural change, and in Japan, this involves addressing some deeply rooted mindsets. The post-WWII success of Japan established a societal model centered around attending elite universities, joining prestigious companies, and working diligently in a harmonious way. This formula helped Japan rise from the ashes, but as society matures, it must embrace diversity—an area where Japan has historically struggled, especially at a cultural level.

One challenge is the influence of older generations, who often encourage young adults to follow the traditional path of securing a stable job with a reputable company. This advice is deeply ingrained and can make it difficult for 18-year-olds to break away from social norms and pursue a different career path. The stigma around alternative careers persists, even though some shifts have occurred. For instance, 30 years ago, no Japanese graduate would have considered working even at top foreign firms , as these were seen as options for those who failed to secure positions at Japan's top companies or in government. Today, while it’s more common to see graduates joining consulting firms like Accenture or McKinsey, the number entering startups remains in single digits. It’s a step forward, but the numbers still need to grow significantly.

Comparing this to my alma mater, Stanford University, where 30% of graduates join startups, the gap with Japanese universities like Tokyo University is stark. Closing this gap is one of my primary goals. I want to show young people the benefits of startups—whether it’s valuable experience, financial rewards, or the enhanced resume they gain from the experience. A major cultural barrier is the belief that once someone joins a company, they are bound to it for life, regardless of circumstances. Changing this mindset requires a broader paradigm shift, particularly among older generations who still view the traditional path as the only viable option and hold a lot of influence over younger generations.

To address this, my company runs an empowerment program designed to educate people about the possibilities within entrepreneurship. For the past decade, we’ve worked with the government to deliver a free program where participants can learn from the lessons I and other venture capitalists and startup founders gathered through our entrepreneurship experiences. The program is open to everyone because I believe that change can come from any motivated individual—not just the elite.

We educate approximately 100 people per year—not a huge number—but over ten years, we’ve built an alumni network of over 1,000 individuals. To me, it’s about sparking a rebellious spirit and planting the seeds of change. I believe this effort will compound over time and gradually shift societal norms. My role is to show people that while the traditional route isn’t necessarily wrong, there are alternative paths that can be just as, if not more, rewarding.

Our company also aims to support those who choose to take the entrepreneurial route, providing guidance and resources to help them succeed. Ultimately, it all comes down to education: equipping people with a clear understanding of both the benefits and risks of entrepreneurship, so they can make informed decisions about their future.

Workshop for corporations

Japan’s startup ecosystem does face valid criticism regarding its lack of exit diversification. Initial public offerings (IPOs) dominate the landscape, occurring at a much higher rate than in other global markets. Additionally, there’s been a longstanding tendency for Japanese startups to focus primarily on the domestic market, often at the expense of global opportunities. How critical do you think diversifying exit strategies is for the long-term health and growth of the Japanese startup ecosystem? Furthermore, how do you see the increasing inflow of foreign capital influencing this landscape?

Diversifying exit strategies is essential for sustaining growth in Japan’s startup ecosystem. While IPOs have their place, the dominance of small IPOs in Japan is problematic. For instance, the Tokyo Pro Market offers a relatively easy route to IPO, but over half of these IPOs have valuations below USD 60 million, akin to a Series A valuation. Such small-scale public listings can be counterproductive, as the costs and regulatory burdens of being a public company far outweigh the benefits for these startups. I've long advocated for greater discipline among securities firms to avoid taking companies public at such low valuations. For example, Goldman Sachs sets a threshold of USD 1 billion for IPOs, a model I believe Japan could benefit from emulating.

Unfortunately, some small companies pursue IPOs driven by ego, with CEOs seeking the status symbol of leading a publicly traded company. However, this practice is shortsighted. Startups are now widely regarded as legitimate ventures, and the world has moved beyond needing IPOs as validation. I've consistently advised companies to avoid going public prematurely unless there’s a compelling reason. Personally, I value independence and believe that being a public company often stifles creativity and innovation.

The slow pace of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) in Japan is another issue. Many large Japanese companies misunderstand global business practices. While they may talk about open innovation and collaboration, they often struggle to execute these concepts due to entrenched habits and a lack of experience. However, I see signs of change. A younger generation of CEOs is emerging, particularly in the financial sector, and they understand the importance of collaboration. As this generation assumes leadership roles, I anticipate a significant increase in M&A activity, particularly in the IT sector, where M&A practices are already gaining traction.

Another critical missing piece in Japan's startup landscape is the secondary market. A strong secondary market provides early investors with a pathway to exit without forcing startups into premature IPOs. In Japan, venture capitalists often push for IPOs within five years to recover their investments, as they lack the longer-term flexibility seen in European fund structures. Without a robust secondary market, companies are pressured into public listings at valuations as low as USD 20 million, which stunts their potential. Developing a secondary market would allow startups to grow organically, enabling them to pursue more substantial IPOs or alternative exits in the future.

Regarding foreign investment, the inward focus of many Japanese startups poses a significant barrier. Most remain domestically oriented, which discourages foreign investors who are looking for globally scalable opportunities. This challenge is compounded by the language barrier, as much of the required documentation is only available in Japanese. For foreign investors, fiduciary responsibilities make it difficult to invest in companies they cannot fully understand, limiting their participation to safe, late-stage deals led by trusted local investors.

To address this, I’ve urged government officials to focus on globalizing the Japanese startup ecosystem. Without this shift, Japan risks lagging behind in producing globally competitive unicorns. While domestic successes like Mercari demonstrate that unicorns are possible in Japan, these cases are exceptions rather than the rule. To build a sustainable pipeline of global unicorns, Japanese startups must adopt English as their working language and focus on international markets from day one. Tools and technologies now exist to facilitate this transition, but it requires a fundamental change in mindset. Companies need to move beyond the domestic-first approach and resist the temptation to rush into low-valuation IPOs for short-term gains.

Looking ahead, I believe that if Japanese startups embrace globalization, the next decade could be transformative. By building teams and products with an international perspective, Japan can reestablish itself as a major contributor to the global economy. My role is to help guide this shift, ensuring that Japan’s startup ecosystem evolves in a way that unlocks its full potential.

In recent years, Japan’s startup ecosystem has indeed expanded to encompass a broader range of investment themes. While traditional strongholds like robotics, healthcare, and entertainment remain significant, newer areas such as Software as a Service (SaaS) and various deep tech fields have brought greater diversity to the market. Given the established strengths of other countries in certain sectors, which markets or themes do you think hold the greatest potential for Japanese startups to distinguish themselves and thrive on a global scale?

I believe Japanese startups should focus on leveraging the country's historical strengths rather than trying to purely compete head-to-head with regions like Silicon Valley or London in areas like AI. Japan's economy has always excelled in hardware rather than software, and while AI is transforming industries globally and is important for national security, the demand for physical objects has and will also remain unwavering.

The United States has dominated the digital space for decades, with companies like Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Tesla, and newer players like OpenAI shaping the landscape. Japan, however, has a distinct advantage in producing high-quality physical products and components, making it well-suited to focus on fields that combine the physical and digital realms, such as robotics and the physical applications of AI.

For instance, the robotics sector is one where Japan can thrive. While it may not dominate the entire field, being a key player in creating innovative robotic solutions or components is critical. Similarly, in emerging fields like quantum computing, Japan already plays a vital role by supplying essential materials and precision devices that make the technology possible. Companies should concentrate on these indispensable components rather than trying to become the next Intel or Apple. Without Japan’s contributions in these areas, groundbreaking technologies like quantum computing simply cannot advance.

Cultural exports, such as anime and manga, further underscore Japan’s strength in creating unique physical and artistic products. While anime has found global success through digital platforms like Netflix, manga remains a notable exception. Manga is often considered an art form, and consumers overwhelmingly prefer physical books over digital versions. This highlights a broader trend: Japan’s ability to create physical products that resonate with emotional or cultural significance.

To directly answer your question, Japan should channel its energy into sectors where it can integrate its manufacturing expertise with emerging technologies, such as robotics and automation: Building advanced robots that solve global challenges in healthcare, manufacturing, and elder care, materials and components for advanced technologies: Developing indispensable components for quantum computing, renewable energy systems, and next-generation devices, and finally, pop culture and creative industries: Capitalizing on its global influence in anime, manga, and gaming, particularly by emphasizing high-quality, physical products. By doubling down on these strengths, Japan can carve out a competitive niche in the global market while avoiding direct competition in purely digital domains. Instead of striving to dominate every sector, Japan should aim to be indispensable in the areas where it has a natural advantage. This strategy will allow Japanese startups to contribute significantly to the global economy while maintaining their unique identity.

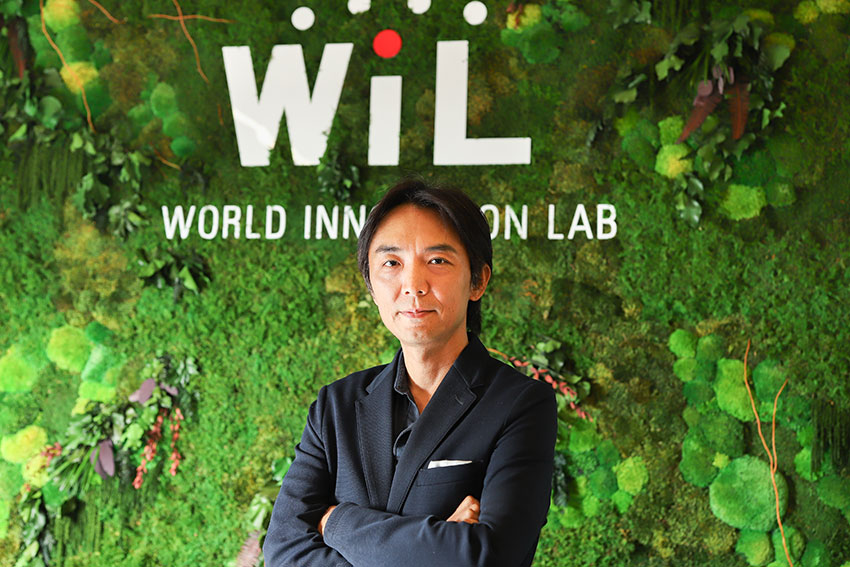

World Innovation Lab (WiL), founded in 2013, has become a transformative force in the venture capital and startup ecosystem in Japan, the U.S., and Asia. By bridging the gap between global startups and Japanese corporations, WiL has not only driven innovation but also played a pivotal role in reshaping corporate and startup collaboration in Japan. With over $2 billion deployed across its strategies in more than 15 unicorns—including Asana and Mercari—WiL has built a track record in key sectors such as AI, fintech, sustainability, and health tech. Could you walk us through the major milestones in WiL’s journey and elaborate on how the company has contributed to the development of Japan’s VC and startup ecosystem?

The establishment of WiL in 2013 was closely aligned with the governmental shift in Japan toward supporting entrepreneurship, as I mentioned earlier. At the time, I realized that Japan required a venture capital model distinct from those in the United States or China. In markets like the U.S., venture capital typically operates by finding talented individuals with groundbreaking ideas who lack the financial resources to scale their businesses. However, in Japan, the challenge lies in the fact that most of the brightest minds gravitate toward large corporations rather than pursuing entrepreneurial paths. This creates a different dynamic, one that requires engaging directly with these corporations to inspire and support potential entrepreneurs from within.

For that reason, the core of WiL’s approach has been to partner with large corporations, earning their trust and positioning ourselves as their "exploration arm." This concept is rooted in the idea of an ambidextrous organization—a framework where companies must balance exploitation (refining existing business operations) with exploration (seeking new opportunities for growth). Many Japanese companies are deeply focused on Kaizen, continuously improving existing operations. However, as industries evolve at an accelerating pace, failing to explore new horizons can be detrimental. That’s where we come in.

WiL helps these companies by connecting them with startups that are inherently geared toward innovation. Startups are always tracking competitors, monitoring market trends, and pivoting their business models in response to new information. Instead of conducting extensive research on behalf of a corporation like Sony, we invest in promising startups and maintain close, ongoing relationships with the entrepreneurs. Through regular one-on-one interactions, we gain invaluable insights into emerging technologies and global trends. This information allows us to guide our corporate partners in identifying new opportunities, while also helping startups access the resources and expertise of these large corporations to scale their innovations.

This model, which I consider to be uniquely suited to Japan, combines the strengths of both startups and large corporations. While startups bring agility, creativity, and a sharp focus on innovation, large corporations provide the capital, talent, and infrastructure to drive these ideas forward on a larger scale. WiL acts as the bridge between these two worlds, fostering collaboration and mutual growth.

When people ask whether WiL is a traditional venture capital firm, my answer is both yes and no. While we invest in startups and aim to promote entrepreneurship, we also actively learn from these startups and leverage their insights to help large corporations adapt and innovate. This collaborative approach aligns with my vision of entrepreneurship in Japan, which emphasizes symbiosis rather than competition.

I also want to emphasize that WiL’s role is not to extract information from startups but to support them. Our reputation and trust with major corporations enable us to facilitate meaningful partnerships between startups and large companies. This approach not only benefits the startups by providing them with the resources they need to grow but also ensures that Japan’s corporations remain competitive in a rapidly changing global landscape. By acting as this bridge, WiL has played a pivotal role in shaping Japan’s venture capital and startup ecosystem, driving innovation through a uniquely Japanese lens.

WiL’s portfolio

WiL manages corporate venture capital initiatives, such as Suzuki Global Ventures, a $100 million fund dedicated to driving innovation in mobility, sustainability, and digital transformation. Beyond Suzuki, WiL partners with other prominent corporations, including Tokio Marine and Fujiyama Bridge Lab. These initiatives serve as a bridge between startups and established companies, employing strategic co-investments, mentorship, and market entry support to scale transformative technologies across sectors like AI, fintech, healthcare, and sustainability. Could you elaborate on how WiL structures these corporate VC partnerships to achieve mutual success?

Some of our corporate partners, like Suzuki and Tokio Marine, have expressed a clear desire to develop their own venture capital capabilities, and I’m eager to support them in this journey. Does this mean they aim to graduate from our partnership? Absolutely not. A reliable partner is always needed, and that’s where we come in. I firmly believe that helping these companies become more startup-friendly and prepared to engage with startups is a positive development. The Japanese approach often involves cultivating access to stocks they value before eventually acquiring them. Suzuki and Tokio Marine have reached a level of open innovation where they’re ready to take the next step and branch out independently. While they still rely on our guidance, they’re now more focused on acquiring promising companies.

Initially, many of our corporate partners understand what startups are but have no clear idea how to engage with them. That’s where we begin—acting as their exploration arm. We identify compelling startups for them, and if they see potential, they can collaborate with these companies or even acquire them. Over time, these partners evolve to invest directly in startups, often with our support.

Every large corporation seeks growth, and for Japanese companies, that growth increasingly comes from overseas markets rather than the domestic one. However, some encountered setbacks during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly with investments in China, which led to significant losses. Now, many of these firms recognize they cannot overlook the U.S. market, despite its complexities. That’s where WiL plays a crucial role, helping them navigate the challenges of working with startups, particularly in the U.S. and European markets. By doing so, we enable these corporations to expand their business bases beyond Japan.

The WiL Ventures III fund, a cornerstone of World Innovation Lab’s $2 billion portfolio, successfully raised $823 million to support growth-stage and late-stage startups worldwide. Focused on transformative sectors such as AI, fintech, sustainability, and healthcare, the fund serves as a bridge between innovative startups and WiL’s extensive Japanese corporate network. With an emphasis on cross-border collaboration, WiL Ventures III aims to drive global expansion for startups while fostering innovation in Japan through strategic co-investments and corporate partnerships. Could you elaborate on the investment themes prioritized by the WiL Ventures III fund and outline the key metrics and objectives it seeks to achieve?

Investments in Japan differ significantly from those in other parts of the world. In Japan, the series or funding stage is less critical than the type of company and its ambitions. A recurring theme in our domestic investments is that these companies aspire to expand overseas. For example, we invested in Mercari because the CEO explicitly stated their goal of winning the U.S. market. In Japan, we look for multi-stage investment opportunities, but the driving force must always be a vision of globalization.

Another factor in Japan is the synergies that startups can create with large corporations. If a big company sees immense potential in a particular technology, they are far more likely to invest. In contrast, the U.S. and Europe prioritize later-stage investments. To become a unicorn, a company must operate on a global scale, and companies like Microsoft, for instance, inevitably enter the Japanese market. This is where WiL plays a key role. We intercept promising foreign startups without a Japanese presence and act as a “tour guide” to help them establish an office, hire a country manager, build a sales team, and more—all facilitated by our firm.

This focus on U.S. and European startups entering Japan ties back to my original mission: to make Japan's entrepreneurial ecosystem vibrant and globally viable. Encouragement alone can only go so far. The most effective way to inspire change is to provide role models. For example, Japan’s baseball industry was revolutionized when Babe Ruth visited; his influence sparked generational talent like Shohei Otani. Similarly, Google, Meta, Amazon, and Apple have already made their mark in Japan. Now, I’m eager to find the next big thing—a foreign startup that can wow the Japanese market and inspire its ecosystem to new heights.

While our fund may resemble a traditional venture capital fund in size and scope, our operating philosophy is distinct. We don’t just focus on profits; we aim to highlight the economy, promote entrepreneurship, and educate people about what is possible. We see our role as having a tangible impact on society, and that’s why we remain committed to our mission.

The world is in a constant state of flux, with rapid changes requiring us to stay ahead. For us, every investment begins with asking, "Why?" We need a clear understanding of what we hope to achieve with each portfolio company. By diversifying our investments, we can address a broader range of objectives. While financial returns are naturally part of the equation—if we invest in good companies, we will make money—we aim to go beyond this. Our focus is on transforming industries, influencing government policies, and redefining how Japan is perceived by foreign startups.

WiL Headquarter

WiL’s geographic diversification strategy spans beyond its bases in Palo Alto and Tokyo to include Europe, alongside its focus on the U.S. and Japan. The company’s first investment in 2015 supported Soracom from its inception, fostering its growth in the global IoT market and culminating in a 2024 Tokyo Stock Exchange listing. Since 2013, WiL has helped brands like Mercari evolve from domestic champions to global successes. In 2021, through partnerships with JETRO and Plug and Play, WiL mentored Japanese startups, facilitating their entry into emerging international markets. Given that other Japanese venture firms also have a presence near Silicon Valley, what do you see as WiL’s comparative advantage? Additionally, what future plans do you have to further enhance your international footprint?

To address the first part of your question, WiL stands out as a unique player in the venture capital space, particularly among Japanese firms. We are one of the few Japanese VCs with a truly significant global presence. Our team in the U.S. comprises seasoned veterans with over two decades of experience, giving us unmatched insight and an expansive network, particularly in Silicon Valley. Compared to any other venture capital firm in Japan, we feel confident that our global reach and expertise give us a distinct competitive edge.

To stay ahead of the competition, we constantly think about what’s next. Whether it’s exploring opportunities in India or another emerging market, we’re always strategizing creative ways to strengthen our competitive advantage.

In the corporate tech sector, WiL’s position is particularly strong. Most venture capital firms primarily raise money from financial institutions and are heavily focused on financial returns. While our investors also care about profitability, their priorities extend beyond that—they value strategy, synergies, and gaining intelligence about global trends. These factors are central to our approach and differentiate us from other firms that focus solely on maximizing profits and achieving quick exits. Financial maximization is not our ultimate goal; rather, we aim to drive strategic impact and influence policy. In the Japanese market, I feel like we’ve established a kind of monopoly. While I recognize that this position may not last forever, we intend to make the most of it while it does.

In foreign markets, the situation is different. One key part of our strategy is investing in other funds. By doing so, we form alliances with major players like Sequoia Capital and Lightspeed Venture Partners. These relationships allow us to collaborate with the best in the industry, rather than compete with them. I position WiL as the ultimate “tour guide” to Japan, offering unmatched access to top talent and opportunities in the Japanese market. This creates a powerful cycle of partnerships and investment.

Japan remains an attractive destination with significant untapped potential, and this approach will continue to draw interest from global firms. My goal is not to compete with these venture capital giants but to complement their efforts. I want them to call us when they find exciting companies, so we can jointly invest and bring those companies into the Japanese market. By refining this strategy, I am confident that WiL will maintain its unique position, as it will be hard to replicate the value we bring to the table.

Imagine that we come back and have this interview again in 2033. What goals or dreams do you hope to achieve by the time we come back for that new interview?

By then, I want my corporate partners to take a much more proactive approach to working with and acquiring startups. Our role will be to serve as an integrator, accelerating the pace of innovation and bringing the potential of our partnerships to fruition in a tangible way. We aim to remain the most trusted and effective exploration arm for our partner companies, continuing to lead the way in fostering innovation and collaboration.

For more information, please visit their website at: https://wilab.com/

0 COMMENTS